An Armenian Invocational Prayer of a Lost Memra of Jacob of Serugh on Good Friday and the Destruction of Sheol

This article grew out of research that began during the first two years of a three-year postdoctoral fellowship at the Department of History at Ghent University (2016-2018), funded by the Research Foundation of Flanders (Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Vlaanderen, FWO), and continued at the Center for the Study of Christianity at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where I took up a one-year postdoctoral research fellowship in 2018-2019. I am thankful to Edward G. Mathews Jr. for offering his advice and corrections to the edition and translation. Thanks are also in order for the reviewers for their generous feedback and suggestions for improvement, especially of the translation. As always, any remaining errors are entirely my own.

This article offers the editio princeps and translation of the Armenian translation of an invocational prayer of a now lost memra of Jacob of Serugh on Good Friday and the destruction of Sheol. This text is different from the Armenian homily on Good Friday which was recently edited and translated by pb. 264 Edward G. Mathews, Jr. On the basis of comparisons with extant homilies of Jacob, it is argued that the prayer is genuine.

I. INTRODUCTION

It was not only Syriac Orthodox Christians who recognized the eloquence of Jacob

of Serugh (d. 29 November 520 or 521), one of the most prolific authors of

homilies of Late Antiquity; other Christian communities did as well. In

particular, Armenian Christians seem to have appreciated his works. As many as

twenty-five of his homilies may have been translated into Armenian, as well as

his Lives of Daniel of Aghlosh and Hannina. 2

On the homilies, see A. Hilkens, “The manuscripts of

the Armenian homilies of Jacob of Serugh: preliminary observations and

checklist” Manuscripta (forthcoming); id., “The

Armenian reception of the homilies of Jacob of Serugh: new findings.” in

Caught in Translation: Studies on Versions of

Late-Antique Christian Literature, Texts and Studies in Eastern

Christianity 17, ed. M. Toca and D. Batovici. Leiden: Brill, 2019,

64–84. For an earlier introduction, which was the inspiration for my

research, see Edward G. Mathews, Jr., “Jacob of Serugh, Homily on Good

Friday and other Armenian treasures: first glances,” in Jacob of Serugh and his times, ed. G. Kiraz

(Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press, 2010), 133–161. The Armenian version of

the Life of Hannina remains unedited but one manuscript witness of the

Life of Daniel was published in L. Ter-Petrosyan, “Jacob of Serugh’s

‘Life of Mar Daniel of Galash,’” Ējmiadzin 36

(1979): 22–40.

A. Hilkens, “The manuscripts of the Armenian homilies”

(forthcoming); id., “‘Beautiful little gems in their own right’:

seventeenth-century Armenian collections of invocational prayers from

Jacob of Serugh’s memre” (to be published in a Festschrift for Sebastian

Brock, edited by M. Hjälm, B. Bitton-Ashkelony and R. Kitchen).

A. Hilkens, “The

Armenian version of Jacob of Serugh’s Memra on the Five Talents,” Le Muséon (forthcoming 2020).

Id., “An Armenian invocational prayer

of a lost homily on Jonah and the Ninevites by Jacob of Serugh” (in

preparation).

This text is

different from (1) the Armenian translation of Jacob’s now lost homily

on the topic of Good Friday and (2) Jacob’s last homily on Mary and

Golgotha, both recently edited and translated in E.G. Mathews, Jr., Jacob of Sarug’s Additional Homilies on Good

Friday (Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press, 2018), as well as (3-4)

from the two homilies edited in P. Bedjan, Homiliae

selectae Mar-Jacobi Sarugensis (Paris: Harrassowitz, 1910)

[repr. P. Bedjan and S.P. Brock, Homilies of Mar Jacob

of Sarug / Homiliae Selectae Mar-Jacobi Sarugensis (Piscataway

NJ: Gorgias Press, 2006)], vol. 2, 522–554 and 554–579, and (3) the turgama on this topic edited and translated by F.

Rilliet, Jacques de Sarough, Six Homélies Festales en

Prose, PO 43.4 (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1986), 610–628.

This brief article presents the editio princeps,

translation, and commentary on the latter text. Currently, only three manuscript

witnesses are known. 7

Some 6500 manuscripts in the Matenadaran await to be catalogued in

detail so it is possible that more witnesses will turn up in the future.

S. Ter-Avetissian,

Katalog der armenischen Handschriften in der

Bibliothek des Klosters in Neu-Djoulfa. Band I (Vienna:

Mekhitarist Press, 1970), 729 (cat. nr. 464). Unfortunately, this

manuscript has remained inaccessible to me until the time of publication

of this article, but the makeup of the collection and the title of the

text as described in the catalogue makes it likely that this is the same

text.

G. Ter-Vardanyan, General catalogue of Armenian manuscripts of the

Mashtots Matenadaran. Volume VII (Yerevan: Nairi, 2012),

813–820.

N. Bogharyan, General Catalogue of the Manuscripts in St. James’

monastery. Volume 5 (Jerusalem: St. James’ Press, 1971),

235–236.

For a brief English introduction to Arak’el

vardapet and a translation of his Lament on the Fall of Constantinople

in 1453, see A.J. Hacikyan, The Heritage of Armenian

Literature. Volume II: From the Sixth to the Eighteenth Century

(Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2000), 668–681. For an

introduction into his corpus of writings (in Armenian), see A. Ghazinyan

and P.M. Khachatryan, Arakʿel of Baghesh (15th

century). Study, critical texts, notes, Medieval Armenian Hymns

8 (Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1971), H.A. Anasyan, Armenian Bibliography 5th-18th cc. Volume 1

(Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1959), col. 1106–1143 and

id., Armenian Bibliography 5th-18th cc. Volume 2

(Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1976), col. 89–151.

Bogharyan’s description of this

manuscript is incomplete: he only mentions the existence of the first

collection and the names of a few authors without identifying any of the

texts. Of the second collection he only identifies three texts, on the

Star (p. 131), on the Ninevites (p. 133) and on Antioch (p. 148) - which

makes it seem as though these texts may be the complete homilies, but in

fact these are only the invocational prayers, surrounded by many other

prologues of homilies that Bogharyan has not mentioned. A complete

description of the contents of these two (and the other) collections

will be provided in Hilkens, “‘Beautiful little gems in their own

right’” (forthcoming). Unfortunately I did not find out about the

presence of the invocational prayer on Good Friday in this manuscript

until after submitting this article to Hugoye for review. During the

limited time that I was able to consult the extensive collection of

Armenian manuscripts in Jerusalem, I only had time to catalogue and

identify the texts in this manuscript but not to copy any of them (aside

from the ones on the Five Talents) nor to compare the version of this

prayer with the one in M 2291. Subsequently I did order images of the

manuscript in question, but unfortunately, due to various factors

including the Covid-19 crisis, these images did not reach me in time

before the pb. 267 publication of this article. That having been

said, judging from my study of the Armenian translation of the

invocational prayer of Jacob’s homily on the Five Talents, which is a

similar case, also being present in M 2291 and twice in J 1499, I would

suggest that the versions of the invocational prayer on Good Friday in J

1499 will probably not vary a great deal, neither from one another nor

from the version in M 2291.

It is worth noting that this text is never explicitly attributed to Jacob of

Serugh. In M 2291 and in the first collection in J 1499 the text remains

anonymous, but in the second collection in J 1499 as well as in NOJ 295, it is

attributed to “the same Jacob” (Նորին Յակոբայ).

13

For the titles,

see above and footnotes 16, 17, and 21 below.

Title:

Նորին սրբոյն Յակոբայ Սրճեցոյ ասացեալ ի

խորհուրդ կիրակէի, “Said by the same holy Jacob of Serugh

about the Mystery of Sunday.”

On this manuscript, see

Ter-Vardanyan, General catalogue, col. 17–20.

Title: նորին սրբոյն յակոբայ

սրճեցոյ ասացեալ ի խորհուրդ կիւրակէի, “Spoken by the same

holy Jacob of Serugh on the Mystery of Sunday.”

Title:

նորին սրբոյն յակոբայ ասացեալ ի խորհուրդ

կիւրակէի, Spoken by the same holy Jacob on the Mystery of

Sunday.” Neither of these texts in this manuscript is mentioned in the

catalogue. I am preparing an edition of this text based on the

accessible witnesses (M 2103, M 2291 and J 1499).

On this

text, see Anasyan, Armenian Bibliography 5th-18th cc.

Volume 1, col. 1141-1142 (nr. 10) who mentions the following

witnesses in addition to M 2291: M 2121, f. 378v-9r, M 745, f.

112v-113r, M 597, f. 53v-54r and M 3457, f. 211v-212r.

The attribution to Jacob of the prayer on Good Friday and the Destruction of

Sheol appears to be correct. The Armenian text seems to be a translation of a

now lost Syriac original, genuinely written by Jacob. The language is very

similar to Jacob’s and some of the imagery that is used in this invocational

prayer is also attested in other homilies by Jacob. 19

Links with characteristics of other

writings by Jacob are explained in the footnotes.

S. Ashbrook Harvey, “Th Poet’s Prayer: Invocational

Prayers in the Mêmrê of Jacob of Sarug,” in Papers

presented at the Seventeenth International Conference on Patristic

Studies held in Oxford 2015, StPatr 78, ed. M. Vinzent, J.

Wickes and K.S. Heal (Turnhout: Brepols, 2017), 51–60, at 53.

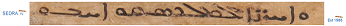

II. EDITION AND TRANSLATION

Ի Մեծի ուրբաթին եւ ի կործանումն դժոխոց

21

As mentioned above,

the title in NOJ 295 and the second collection in J 1499 is preceded by

the words Նորին Յակոբայ ասացեալ,

“Spoken/dictated by the same Jacob”, but because my edition is based on

M 2291, I have not added those words to the text.

The link between the crucifixion and the destruction of Sheol also appears in Jacob’s last and unfinished homily, on Mary and Golgotha: “when the one slain cries out in a [loud] voice and the walls of Sheol have fallen” (Mathews, Jacob of Sarug’s Additional Homilies, 78, ll. 33–34). See also T. Kollamparampil, Salvation in Christ according to Jacob of Serugh: An exegetico-theological study on the homilies of Jacob of Serugh on the Feasts of Our Lord, Gorgias Dissertations in Early Christian Studies 49 (Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press, 2010), 210–211.

O Christ, the one who gives light to the universe, illuminate my obscured mind to preach about you. 23See also in the Armenian homily on Good Friday: “the mind that has seen You is illumined by You to speak of what it has received from You” (Mathews, Jacob of Sarug’s Additional Homilies, 33, ll. 12–13) and “O day-star, great sun, spread forth Your rays into my dark heart, that I may be illumined to speak of You in a worthy manner” (Mathews, Jacob of Sarug’s Additional Homilies, 33, ll. 18–20). For Jacob’s use of the imagery of light and darkness, see Kollamparampil, Salvation in Christ, 345–347.

Grant me from your mercy, 24In this text, the term ողորմութիւն is consistently used to render the idea of mercy. In the case of the Armenian version of Jacob’s homily on the Five Talents, or at least the Armenian equivalent of its invocational prayer, ողորմութիւն appears as the counterpart to two Syriac words that can be rendered as “mercy”, ܚܢܢܐ and ܪ̈ܚܡܐ, see Hilkens, “The Armenian version” (forthcoming). On ܚܢܢܐ, divine mercy, in Jacob’s oeuvre, see Kollamparampil, Salvation in Christ, 206–207.

pb. 271 so that through your mercy I may comprehend your love of humanity. Grant me grace to preach about you, so that all who listen may turn away in penance from their evil deeds. Touch me through love from your beneficence to proclaim 25The verb that is used here is քարոզել, k’arozel, from the Syriac ܟܪܙ. The same word is used in line 5, where I have translated it as “to preach”.

your glory to humanity, so that those who listen may entreat you to forgive trespasses. Send to me the protector, 26The word պահպանիչ also means “blessing”, but the translation “guardian, protector” makes more sense in this context. I am thankful to the anonymous reviewer for this and several other suggestions for improvement of the translation.

your Holy Spirit, so that through It I may be strengthened 27Because I have only inspected the text in M 2291, I am hesitant to correct the indicative present զօրանամ (zōranam), but I would suggest that the translation may have originally contained the subjunctive զօրասցի (zōrasc’i), hence my translation “so that through It I may be strengthened” rather than “for through It I am strengthened”. Having said that, this error may also be present in the other witnesses. In the case of the Armenian version of the invocational prayer of Jacob’s homily on the Five Talents, for instance, all four witnesses that I have seen contain the same error in the equivalent of verse 18: առաքինութիւն (aṙak’inut’iwn) instead of առաքելութիւն (aṙak’elut’iwn), the latter of which is the equivalent of ܫܠܝܚܘܬܐ, “mission”, which is in the Syriac text, see Hilkens, “The Armenian version” (forthcoming).

to speak about your invincible force. As you destroyed the walls of Jericho by the sound of the horn, 28Josh 6:1–27. Jacob also evokes the fall of Jericho in his homily on the veil of Moses, where he compares it to Christ’s overthrowing of Sheol, see Kollamparampil, Salvation in Christ, 196 n 138 and 332.

so also now give grace to the sound of my preaching to destroy the stronghold of the enemy. 29For Jacob’s use of military language, see e.g. A. McCollum, Jacob of Sarug’s Homilies on Jesus’ Temptation, Texts from Christian Late Antiquity 38, The Metrical Homilies of Mar Jacob of Sarug 33 (Piscataway NJ: Gorgias pb. 272 Press, 2014) and A. Hilkens, “Rhetoric in Jacob of Serugh’s Mimro on St. George the Martyr,” in Rhetoric and historiography, ed. L. Van Hoof and M. Conterno, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (forthcoming). In the homily on St. George, for instance, Jacob urges his hearers to build strongholds (ܚܣ̈ܢܐ): “Blessed are you who make fortified strongholds that cannot be captured, in which those who flee from Satan take refuge” (Bedjan and Brock, Homilies / Homiliae, vol. 5, 770, l. 4).

(You) who by the sprinkling 30Here, the idea of sprinkling is rendered in Armenian with the noun սրսկումն (srskumn, ‛sprinkling’). In the next verse an entirely different root is used, which suggests perhaps that Jacob himself also used two different Syriac roots.

of your blood sanctified the furnishings of the tabernacle, 31Presumably this is the “tabernacle of mysteries”, the “house for the holy things”, the “house for the mysteries” that was built by Melchizedek, like the altar that was built by Abraham and Isaac on Golgotha, the site of the crucifixion, at least according to Jacob. Here it is not a metaphor for Christ himself, but for the Church, which was sanctified by the blood that flowed out of Christ’s side, see A.B. Elkhoury, Types and Symbols of the Church in the Writings of Jacob of Serugh, PhD Dissertation, Katholische Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt 2017, 56 and 69–71. There may also be links with the unstudied homily on the Mystery of the Tabernacle of which the editio princeps appeared recently, R. Akhrass and I. Syryany, 160 Unpublished Homilies of Jacob of Serugh, 2 vols. (Damascus: Department of Syriac Studies, Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate, 2017), vol. 2, 174–191. A study of this homily could also be useful on another level, as it was also translated into Armenian. The diplomatic edition of the Armenian text, based on an unknown manuscript, was published in Spiritual writings and homilies (Constantinople, 1722), 388–410. Only three Armenian manuscripts are known, two manuscripts in the Armenian Patriarchate in Jerusalem (154c, pp. 1552–1561, copied in 1737, and 1365, fols. 52v-83v of unknown date) as well as a late copy in the Matenadaran, M 2786, fols. 129v-135r (19th c.).

so also now sprinkle your mercy on me. 32Jacob also uses the image of the sprinkling of mercy in his homily on the Ascension: “He walked on the earth and sprinkled mercy and filled it with hope” (Kollamparampil, Salvation in Christ, 207). For the edition and translation of this homily, see P. Bedjan, S. Martyrii, qui et Sahdona, quae supersunt omnia, Paris-Leipzig: Harrassowitz, 1902, 808–832 (at 812, l. 17; repr. in P. Bedjan, Cantus seu Homiliae Mar Jacobi in Jesum et Mariam, Paris-Leipzig: Harrassowitz, 1902, 169–220 and Bedjan and Brock, Homiliae / Homilies, vol. 6, 196–220). A vocalized version of this pb. 273 edition, furnished with an English translation, can be found in T. Kollamparampil, Jacob of Sarug’s Homily on the Ascension of Our Lord, Texts from Late Antiquity 24, The Metrical Homilies of Jacob of Sarug 21 (Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press, 2010). In the Armenian translation of the homily on the Ascension the verb ցօղեմ, derived from the noun ցօղ, “dew,” is used to render the verb ܪܰܣ, “to sprinkle,” see Գիրք եւ ճառ հոգեշահ [Spiritual writings and homilies], 345–369 (at 350) as well as the draft edition of Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. arm. 116, fols. 319r-322v (AD 1307), prepared by Alin Suciu and available on his Academia.edu page: շրջեցաւ յերկրի (P 116: յաշխարհի), և ցօղեաց ի նա զգութ իւր, և ելից զնա յուսով, “He went around the earth, he sprinkled his mercy on it, and he filled it with hope.” That the translator of the invocational prayer from the homily on Good Friday and the Destruction of Sheol used ցօղեա, the imperative form of this verb, in this verse suggests that the verb ܪܰܣ may have appeared in the Syriac Vorlage. However, note also how in the Armenian version of the homily on the Ascension, ܚܢܢܐ (“mercy”) is rendered as գութ rather than ողորմութիւն, which could suggest the involvement of a different translator.

pb. 273 By your finger 33Perhaps alluding to Lev 4:5–6, which describes how during the sacrifice at the tabernacle, the priest dips his finger in the blood and sprinkles the blood seven times before the veil.

you granted illumination to the great Moses to proclaim your divinity, so also now illuminate me by the dawning 34Presumably ծագմամբ is the equivalent of ܒܕܢܚܐ. In the Armenian version of Jacob’s Memra on the Star that appeared to the Magi and on the Slaughter of Infants ܒܕܢܚܐ, the very first word, was rendered as ծագումն. For the Syriac text of this homily, see Bedjan, Homiliae selectae, vol.1, 84–153 (first word of line 1), translated into English by N. Macabasag, “Jacob of Serugh’s Memra on the Star that appeared to the Magi and on the Slaughter of Infants (vat. syr. 118)”, Parole de l’Orient 43 (2017): 237–302. The Armenian text is unedited. So far, I have only identified six manuscripts of the Armenian translation, the oldest manuscript being ms. 1, fols. 20v-37v, in the collection of the Mekhitarist fathers in Vienna. In this manuscript, the text is incorrectly ascribed to Jacob of Nisibis. This misattribution also occurs in the most recent witness, ms. 1286, fols. 5r-10v (dated 1820), in the collection of the Mekhitarist fathers in Venice.

of your light, 35For the idea of the dawning of the sun on the mind, see e.g. Jacob’s second homily on Elissaeus and on the King of Moab (Bedjan, Homiliae selectae, vol. 4, 282, l. 6–7; Kollamparampil, Salvation in Christ, 387).

pb. 274 so that by your light I may illuminate 36On illumination, see above.

the sons 37The Vorlage of որդիք, “sons”, is most likely ܒܢ̈ܝ, which literally means “sons”, but can be translated more generally as “children (of your church).”

of your church. Sons 38Here the translation as “sons” is fairly certain, given that it acts as a counterpart to the “daughters of Sion”.

of the bride of the church, receive the words of the bridegroom 39On Jacob’s use of this popular and much older theme of the Church as the bride of Christ who is the bridegroom (Mk 2:19–20; Jn 3:29; Eph 5:25–27; 2 Cor 11:2), see e.g. Elkhoury, Types and Symbols, 221. The theme is also used in the Armenian homily on Good Friday, Mathews, Jacob of Sarug’s Additional Homilies, 82.

and daughters of Zion, 40Cf. Zech 9:9; Jn 12:15; Mt 21:5. Jacob uses this term in the singular to refer to Israel, see Kollamparampil Salvation, 156–157, 254, 256 and Elkhoury, Types and Symbols, 292, 294.

listen to my homily 41The Armenian word քարոզ k‛aroz is used for a homily here. In the translation of the invocational prayer of the homily on the Five Talents, memra is consistently translated as ճառ, a word commonly used to refer to homilies, but which has the basic meaning of “discourse”. This may suggest that the word քարոզ k‛aroz here, was used by the compiler of the invocational prayers, who appears to have made alterations to the last verses of several other invocational prayers as well, see Hilkens, “The Armenian version” (forthcoming).

.- Akhrass R. and I. Syryany. 160 Unpublished Homilies of Jacob of Serugh, 2 vols. Damascus: Department of Syriac Studies, Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate, 2017.

- Anasyan, H.A. Armenian Bibliography 5th-18th cc. Volume 1. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1959.

- Anasyan, H.A. Armenian Bibliography 5th-18th cc. Volume 2. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1976.

- Ashbrook Harvey, S. “The Poet’s Prayer: Invocational Prayers in the Mêmrê of Jacob of Sarug.” In Papers presented at the Seventeenth International Conference on Patristic Studies held in Oxford 2015, StPatr 78, ed. M. Vinzent, J. Wickes and K.S. Heal. Turnhout: Brepols, 2017.

- Bedjan, P. Cantus seu Homiliae Mar Jacobi in Jesum et Mariam, Paris-Leipzig: Harrassowitz, 1902.

- Bedjan, P. Homiliae selectae Mar-Jacobi Sarugensis. 5 vols. Paris: Harrassowitz, 1910 [repr. Bedjan P. and Brock, S.P. Homilies of Mar Jacob of Sarug / Homiliae Selectae Mar-Jacobi Sarugensis, 6 vols. Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press, 2006.

- Bogharyan, N., General Catalogue of the Manuscripts in St. James’ monastery. Volume 5. Jerusalem: St. James’ Press, 1971. .

- Elkhoury, A.B. Types and Symbols of the Church in the Writings of Jacob of Serugh. PhD Dissertation, Katholische Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt, 2017.

- Ghazinyan, A. and P.M. Khachatryan, Arak’el of Baghesh (15th century). Study, critical texts, notes, Medieval Armenian Hymns 8, Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1971.

- Hacikyan, A.J. The Heritage of Armenian Literature. Volume II: From the Sixth to the Eighteenth Century. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2000.

- Hilkens, A. “The Armenian reception of the homilies of Jacob of Serugh: new findings.” In Caught in Translation: Studies on Versions of Late-Antique Christian Literature, Texts and Studies in Eastern Christianity 17, ed. M. Toca and D. Batovici. Leiden: Brill, 2019.

- Hilkens, A. “Rhetoric in Jacob of Serugh’s Mimro on St. George the Martyr.” In Rhetoric and historiography, ed. L. Van Hoof and M. Conterno. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (forthcoming).

- Hilkens, A. “The manuscripts of the Armenian homilies of Jacob of Serugh: preliminary observations and checklist” Manuscripta (forthcoming 2020).

- Hilkens, A. “‘Beautiful little gems in their own right’: seventeenth-century Armenian collections of invocational prayers from Jacob of Serugh’s memre” (forthcoming in a Festschrift for Sebastian Brock, edited by M. Hjälm, B. Bitton-Ashkelony and R. Kitchen).

- Hilkens, A. “The Armenian version of Jacob of Serugh’s Memra on the Five Talents,” Le Muséon (forthcoming 2020).

- Kollamparampil, T. Salvation in Christ according to Jacob of Serugh: An exegetico-theological study on the homilies of Jacob of Serugh on the Feasts of Our Lord, Gorgias Dissertations in Early Christian Studies 49. Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press, 2010.

- Kollamparampil, T. Jacob of Sarug’s Homily on the Ascension of Our Lord, Texts from Late Antiquity 24. The Metrical homilies of Jacob of Sarug 21. Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press, 2010.

- Macabasag, N. “Jacob of Serugh’s Memra on the Star that appeared to the Magi and on the Slaughter of Infants (vat. syr. 118).” Parole de l’Orient 43 (2017): 237–302.

- Mathews, Jr., E.G. “Jacob of Serugh, Homily on Good Friday and other Armenian treasures: first glances.” In Jacob of Serugh and his times, ed. G. Kiraz, Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press, 2010.

- Mathews, Jr., E.G. Jacob of Sarug’s Additional Homilies on Good Friday. Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press: 2018.

- McCollum, A. Jacob of Sarug’s Homilies on Jesus’ Temptation, Texts from Christian Late Antiquity 38. The Metrical Homilies of Mar Jacob of Sarug 33. Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press, 2014.

- Rilliet, F. Jacques de Sarough, Six Homélies Festales en Prose, PO 43.4. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1986.

- Ter-Avetissian, S. Katalog der armenischen Handschriften in der Bibliothek des Klosters in Neu-Djoulfa. Band I. Vienna: Mekhitarist Press, 1970.

- Ter-Petrosyan, L. “Jacob of Serugh’s ‘Life of Mar Daniel of Galash’”, Ējmiadzin 36 (1979): 22–40.

- Ter-Vardanyan, G. General catalogue of Armenian manuscripts of the Mashtots Matenadaran. Volume VII. Yerevan: Nairi, 2012.

- Spiritual writings and homilies. Constantinople, 1722.

Footnotes

1 This article grew out of research that began during the first two years of a three-year postdoctoral fellowship at the Department of History at Ghent University (2016-2018), funded by the Research Foundation of Flanders (Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Vlaanderen, FWO), and continued at the Center for the Study of Christianity at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where I took up a one-year postdoctoral research fellowship in 2018-2019. I am thankful to Edward G. Mathews Jr. for offering his advice and corrections to the edition and translation. Thanks are also in order for the reviewers for their generous feedback and suggestions for improvement, especially of the translation. As always, any remaining errors are entirely my own.

2 On the homilies, see A. Hilkens, “The manuscripts of the Armenian homilies of Jacob of Serugh: preliminary observations and checklist” Manuscripta (forthcoming); id., “The Armenian reception of the homilies of Jacob of Serugh: new findings.” in Caught in Translation: Studies on Versions of Late-Antique Christian Literature, Texts and Studies in Eastern Christianity 17, ed. M. Toca and D. Batovici. Leiden: Brill, 2019, 64–84. For an earlier introduction, which was the inspiration for my research, see Edward G. Mathews, Jr., “Jacob of Serugh, Homily on Good Friday and other Armenian treasures: first glances,” in Jacob of Serugh and his times, ed. G. Kiraz (Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press, 2010), 133–161. The Armenian version of the Life of Hannina remains unedited but one manuscript witness of the Life of Daniel was published in L. Ter-Petrosyan, “Jacob of Serugh’s ‘Life of Mar Daniel of Galash,’” Ējmiadzin 36 (1979): 22–40.

3 A. Hilkens, “The manuscripts of the Armenian homilies” (forthcoming); id., “‘Beautiful little gems in their own right’: seventeenth-century Armenian collections of invocational prayers from Jacob of Serugh’s memre” (to be published in a Festschrift for Sebastian Brock, edited by M. Hjälm, B. Bitton-Ashkelony and R. Kitchen).

4 A. Hilkens, “The Armenian version of Jacob of Serugh’s Memra on the Five Talents,” Le Muséon (forthcoming 2020).

5 Id., “An Armenian invocational prayer of a lost homily on Jonah and the Ninevites by Jacob of Serugh” (in preparation).

6 This text is different from (1) the Armenian translation of Jacob’s now lost homily on the topic of Good Friday and (2) Jacob’s last homily on Mary and Golgotha, both recently edited and translated in E.G. Mathews, Jr., Jacob of Sarug’s Additional Homilies on Good Friday (Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press, 2018), as well as (3-4) from the two homilies edited in P. Bedjan, Homiliae selectae Mar-Jacobi Sarugensis (Paris: Harrassowitz, 1910) [repr. P. Bedjan and S.P. Brock, Homilies of Mar Jacob of Sarug / Homiliae Selectae Mar-Jacobi Sarugensis (Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press, 2006)], vol. 2, 522–554 and 554–579, and (3) the turgama on this topic edited and translated by F. Rilliet, Jacques de Sarough, Six Homélies Festales en Prose, PO 43.4 (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1986), 610–628.

7 Some 6500 manuscripts in the Matenadaran await to be catalogued in detail so it is possible that more witnesses will turn up in the future.

8 S. Ter-Avetissian, Katalog der armenischen Handschriften in der Bibliothek des Klosters in Neu-Djoulfa. Band I (Vienna: Mekhitarist Press, 1970), 729 (cat. nr. 464). Unfortunately, this manuscript has remained inaccessible to me until the time of publication of this article, but the makeup of the collection and the title of the text as described in the catalogue makes it likely that this is the same text.

9 G. Ter-Vardanyan, General catalogue of Armenian manuscripts of the Mashtots Matenadaran. Volume VII (Yerevan: Nairi, 2012), 813–820.

10 N. Bogharyan, General Catalogue of the Manuscripts in St. James’ monastery. Volume 5 (Jerusalem: St. James’ Press, 1971), 235–236.

11 For a brief English introduction to Arak’el vardapet and a translation of his Lament on the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, see A.J. Hacikyan, The Heritage of Armenian Literature. Volume II: From the Sixth to the Eighteenth Century (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2000), 668–681. For an introduction into his corpus of writings (in Armenian), see A. Ghazinyan and P.M. Khachatryan, Arakʿel of Baghesh (15th century). Study, critical texts, notes, Medieval Armenian Hymns 8 (Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1971), H.A. Anasyan, Armenian Bibliography 5th-18th cc. Volume 1 (Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1959), col. 1106–1143 and id., Armenian Bibliography 5th-18th cc. Volume 2 (Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1976), col. 89–151.

12 Bogharyan’s description of this manuscript is incomplete: he only mentions the existence of the first collection and the names of a few authors without identifying any of the texts. Of the second collection he only identifies three texts, on the Star (p. 131), on the Ninevites (p. 133) and on Antioch (p. 148) - which makes it seem as though these texts may be the complete homilies, but in fact these are only the invocational prayers, surrounded by many other prologues of homilies that Bogharyan has not mentioned. A complete description of the contents of these two (and the other) collections will be provided in Hilkens, “‘Beautiful little gems in their own right’” (forthcoming). Unfortunately I did not find out about the presence of the invocational prayer on Good Friday in this manuscript until after submitting this article to Hugoye for review. During the limited time that I was able to consult the extensive collection of Armenian manuscripts in Jerusalem, I only had time to catalogue and identify the texts in this manuscript but not to copy any of them (aside from the ones on the Five Talents) nor to compare the version of this prayer with the one in M 2291. Subsequently I did order images of the manuscript in question, but unfortunately, due to various factors including the Covid-19 crisis, these images did not reach me in time before the pb. 267 publication of this article. That having been said, judging from my study of the Armenian translation of the invocational prayer of Jacob’s homily on the Five Talents, which is a similar case, also being present in M 2291 and twice in J 1499, I would suggest that the versions of the invocational prayer on Good Friday in J 1499 will probably not vary a great deal, neither from one another nor from the version in M 2291.

13 For the titles, see above and footnotes 16, 17, and 21 below.

14 Title: Նորին սրբոյն Յակոբայ Սրճեցոյ ասացեալ ի խորհուրդ կիրակէի, “Said by the same holy Jacob of Serugh about the Mystery of Sunday.”

15 On this manuscript, see Ter-Vardanyan, General catalogue, col. 17–20.

16 Title: նորին սրբոյն յակոբայ սրճեցոյ ասացեալ ի խորհուրդ կիւրակէի, “Spoken by the same holy Jacob of Serugh on the Mystery of Sunday.”

17 Title: նորին սրբոյն յակոբայ ասացեալ ի խորհուրդ կիւրակէի, Spoken by the same holy Jacob on the Mystery of Sunday.” Neither of these texts in this manuscript is mentioned in the catalogue. I am preparing an edition of this text based on the accessible witnesses (M 2103, M 2291 and J 1499).

18 On this text, see Anasyan, Armenian Bibliography 5th-18th cc. Volume 1, col. 1141-1142 (nr. 10) who mentions the following witnesses in addition to M 2291: M 2121, f. 378v-9r, M 745, f. 112v-113r, M 597, f. 53v-54r and M 3457, f. 211v-212r.

19 Links with characteristics of other writings by Jacob are explained in the footnotes.

20 S. Ashbrook Harvey, “Th Poet’s Prayer: Invocational Prayers in the Mêmrê of Jacob of Sarug,” in Papers presented at the Seventeenth International Conference on Patristic Studies held in Oxford 2015, StPatr 78, ed. M. Vinzent, J. Wickes and K.S. Heal (Turnhout: Brepols, 2017), 51–60, at 53.

21 As mentioned above, the title in NOJ 295 and the second collection in J 1499 is preceded by the words Նորին Յակոբայ ասացեալ, “Spoken/dictated by the same Jacob”, but because my edition is based on M 2291, I have not added those words to the text.

22 The link between the crucifixion and the destruction of Sheol also appears in Jacob’s last and unfinished homily, on Mary and Golgotha: “when the one slain cries out in a [loud] voice and the walls of Sheol have fallen” (Mathews, Jacob of Sarug’s Additional Homilies, 78, ll. 33–34). See also T. Kollamparampil, Salvation in Christ according to Jacob of Serugh: An exegetico-theological study on the homilies of Jacob of Serugh on the Feasts of Our Lord, Gorgias Dissertations in Early Christian Studies 49 (Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press, 2010), 210–211.

23 See also in the Armenian homily on Good Friday: “the mind that has seen You is illumined by You to speak of what it has received from You” (Mathews, Jacob of Sarug’s Additional Homilies, 33, ll. 12–13) and “O day-star, great sun, spread forth Your rays into my dark heart, that I may be illumined to speak of You in a worthy manner” (Mathews, Jacob of Sarug’s Additional Homilies, 33, ll. 18–20). For Jacob’s use of the imagery of light and darkness, see Kollamparampil, Salvation in Christ, 345–347.

24 In this text, the term ողորմութիւն is consistently used to render the idea of mercy. In the case of the Armenian version of Jacob’s homily on the Five Talents, or at least the Armenian equivalent of its invocational prayer, ողորմութիւն appears as the counterpart to two Syriac words that can be rendered as “mercy”, ܚܢܢܐ and ܪ̈ܚܡܐ, see Hilkens, “The Armenian version” (forthcoming). On ܚܢܢܐ, divine mercy, in Jacob’s oeuvre, see Kollamparampil, Salvation in Christ, 206–207.

25 The verb that is used here is քարոզել, k’arozel, from the Syriac ܟܪܙ. The same word is used in line 5, where I have translated it as “to preach”.

26 The word պահպանիչ also means “blessing”, but the translation “guardian, protector” makes more sense in this context. I am thankful to the anonymous reviewer for this and several other suggestions for improvement of the translation.

27 Because I have only inspected the text in M 2291, I am hesitant to correct the indicative present զօրանամ (zōranam), but I would suggest that the translation may have originally contained the subjunctive զօրասցի (zōrasc’i), hence my translation “so that through It I may be strengthened” rather than “for through It I am strengthened”. Having said that, this error may also be present in the other witnesses. In the case of the Armenian version of the invocational prayer of Jacob’s homily on the Five Talents, for instance, all four witnesses that I have seen contain the same error in the equivalent of verse 18: առաքինութիւն (aṙak’inut’iwn) instead of առաքելութիւն (aṙak’elut’iwn), the latter of which is the equivalent of ܫܠܝܚܘܬܐ, “mission”, which is in the Syriac text, see Hilkens, “The Armenian version” (forthcoming).

28 Josh 6:1–27. Jacob also evokes the fall of Jericho in his homily on the veil of Moses, where he compares it to Christ’s overthrowing of Sheol, see Kollamparampil, Salvation in Christ, 196 n 138 and 332.

29 For Jacob’s use of military language, see e.g. A. McCollum, Jacob of Sarug’s Homilies on Jesus’ Temptation, Texts from Christian Late Antiquity 38, The Metrical Homilies of Mar Jacob of Sarug 33 (Piscataway NJ: Gorgias pb. 272 Press, 2014) and A. Hilkens, “Rhetoric in Jacob of Serugh’s Mimro on St. George the Martyr,” in Rhetoric and historiography, ed. L. Van Hoof and M. Conterno, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (forthcoming). In the homily on St. George, for instance, Jacob urges his hearers to build strongholds (ܚܣ̈ܢܐ): “Blessed are you who make fortified strongholds that cannot be captured, in which those who flee from Satan take refuge” (Bedjan and Brock, Homilies / Homiliae, vol. 5, 770, l. 4).

30 Here, the idea of sprinkling is rendered in Armenian with the noun սրսկումն (srskumn, ‛sprinkling’). In the next verse an entirely different root is used, which suggests perhaps that Jacob himself also used two different Syriac roots.

31 Presumably this is the “tabernacle of mysteries”, the “house for the holy things”, the “house for the mysteries” that was built by Melchizedek, like the altar that was built by Abraham and Isaac on Golgotha, the site of the crucifixion, at least according to Jacob. Here it is not a metaphor for Christ himself, but for the Church, which was sanctified by the blood that flowed out of Christ’s side, see A.B. Elkhoury, Types and Symbols of the Church in the Writings of Jacob of Serugh, PhD Dissertation, Katholische Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt 2017, 56 and 69–71. There may also be links with the unstudied homily on the Mystery of the Tabernacle of which the editio princeps appeared recently, R. Akhrass and I. Syryany, 160 Unpublished Homilies of Jacob of Serugh, 2 vols. (Damascus: Department of Syriac Studies, Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate, 2017), vol. 2, 174–191. A study of this homily could also be useful on another level, as it was also translated into Armenian. The diplomatic edition of the Armenian text, based on an unknown manuscript, was published in Spiritual writings and homilies (Constantinople, 1722), 388–410. Only three Armenian manuscripts are known, two manuscripts in the Armenian Patriarchate in Jerusalem (154c, pp. 1552–1561, copied in 1737, and 1365, fols. 52v-83v of unknown date) as well as a late copy in the Matenadaran, M 2786, fols. 129v-135r (19th c.).

32 Jacob also uses the image of the sprinkling of mercy in his homily on the Ascension: “He walked on the earth and sprinkled mercy and filled it with hope” (Kollamparampil, Salvation in Christ, 207). For the edition and translation of this homily, see P. Bedjan, S. Martyrii, qui et Sahdona, quae supersunt omnia, Paris-Leipzig: Harrassowitz, 1902, 808–832 (at 812, l. 17; repr. in P. Bedjan, Cantus seu Homiliae Mar Jacobi in Jesum et Mariam, Paris-Leipzig: Harrassowitz, 1902, 169–220 and Bedjan and Brock, Homiliae / Homilies, vol. 6, 196–220). A vocalized version of this pb. 273 edition, furnished with an English translation, can be found in T. Kollamparampil, Jacob of Sarug’s Homily on the Ascension of Our Lord, Texts from Late Antiquity 24, The Metrical Homilies of Jacob of Sarug 21 (Piscataway NJ: Gorgias Press, 2010). In the Armenian translation of the homily on the Ascension the verb ցօղեմ, derived from the noun ցօղ, “dew,” is used to render the verb ܪܰܣ, “to sprinkle,” see Գիրք եւ ճառ հոգեշահ [Spiritual writings and homilies], 345–369 (at 350) as well as the draft edition of Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. arm. 116, fols. 319r-322v (AD 1307), prepared by Alin Suciu and available on his Academia.edu page: շրջեցաւ յերկրի (P 116: յաշխարհի), և ցօղեաց ի նա զգութ իւր, և ելից զնա յուսով, “He went around the earth, he sprinkled his mercy on it, and he filled it with hope.” That the translator of the invocational prayer from the homily on Good Friday and the Destruction of Sheol used ցօղեա, the imperative form of this verb, in this verse suggests that the verb ܪܰܣ may have appeared in the Syriac Vorlage. However, note also how in the Armenian version of the homily on the Ascension, ܚܢܢܐ (“mercy”) is rendered as գութ rather than ողորմութիւն, which could suggest the involvement of a different translator.

33 Perhaps alluding to Lev 4:5–6, which describes how during the sacrifice at the tabernacle, the priest dips his finger in the blood and sprinkles the blood seven times before the veil.

34 Presumably ծագմամբ is the equivalent of ܒܕܢܚܐ. In the Armenian version of Jacob’s Memra on the Star that appeared to the Magi and on the Slaughter of Infants ܒܕܢܚܐ, the very first word, was rendered as ծագումն. For the Syriac text of this homily, see Bedjan, Homiliae selectae, vol.1, 84–153 (first word of line 1), translated into English by N. Macabasag, “Jacob of Serugh’s Memra on the Star that appeared to the Magi and on the Slaughter of Infants (vat. syr. 118)”, Parole de l’Orient 43 (2017): 237–302. The Armenian text is unedited. So far, I have only identified six manuscripts of the Armenian translation, the oldest manuscript being ms. 1, fols. 20v-37v, in the collection of the Mekhitarist fathers in Vienna. In this manuscript, the text is incorrectly ascribed to Jacob of Nisibis. This misattribution also occurs in the most recent witness, ms. 1286, fols. 5r-10v (dated 1820), in the collection of the Mekhitarist fathers in Venice.

35 For the idea of the dawning of the sun on the mind, see e.g. Jacob’s second homily on Elissaeus and on the King of Moab (Bedjan, Homiliae selectae, vol. 4, 282, l. 6–7; Kollamparampil, Salvation in Christ, 387).

36 On illumination, see above.

37 The Vorlage of որդիք, “sons”, is most likely ܒܢ̈ܝ, which literally means “sons”, but can be translated more generally as “children (of your church).”

38 Here the translation as “sons” is fairly certain, given that it acts as a counterpart to the “daughters of Sion”.

39 On Jacob’s use of this popular and much older theme of the Church as the bride of Christ who is the bridegroom (Mk 2:19–20; Jn 3:29; Eph 5:25–27; 2 Cor 11:2), see e.g. Elkhoury, Types and Symbols, 221. The theme is also used in the Armenian homily on Good Friday, Mathews, Jacob of Sarug’s Additional Homilies, 82.

40 Cf. Zech 9:9; Jn 12:15; Mt 21:5. Jacob uses this term in the singular to refer to Israel, see Kollamparampil Salvation, 156–157, 254, 256 and Elkhoury, Types and Symbols, 292, 294.

41 The Armenian word քարոզ k‛aroz is used for a homily here. In the translation of the invocational prayer of the homily on the Five Talents, memra is consistently translated as ճառ, a word commonly used to refer to homilies, but which has the basic meaning of “discourse”. This may suggest that the word քարոզ k‛aroz here, was used by the compiler of the invocational prayers, who appears to have made alterations to the last verses of several other invocational prayers as well, see Hilkens, “The Armenian version” (forthcoming).